[This is the first of a series of articles that seek to reflect on the ways in which social mobilization, creation of space, and new modes of resistance intersect within the Sahrawi community. Between these grooves are nuanced conceptions of Sahrawi identity that are colored by varied experiences but a shared memory of external domination and displacement. The series is informed by research conducted during a weeklong stay in the Dakhla refugee camp, located about one hundred miles southeast of Tindouf. A week is nowhere near sufficient to fully grasp the over forty years Sahrawi refugees have lived in these conditions and away from their land. A week, however, is sufficient to dispel dominant political and historical narratives that have dominated knowledge production on the Western Saharan conflict. Jadaliyya has begun tackling these narratives on the conflict, most notably through the publication of roundtable entitled “Beyond the Dominant Narratives on the Western Sahara” and a survey conducted with Sahrawis experiencing different living conditions. Building on these earlier contributions, this series is an attempt to contribute to the conversation on the Western Saharan conflict in a meaningful manner.]

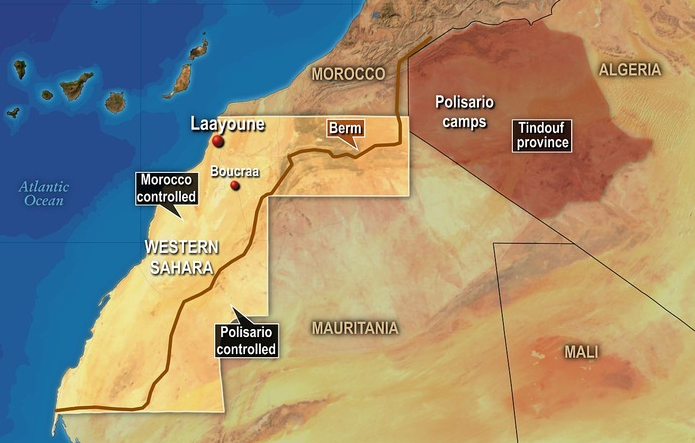

A benign online search for a map that outlines the geographical area between southern Morocco, southwestern Algeria, and the Western Sahara will yield a number of results. Some maps will have solid borders between Morocco, Algeria, and the Western Sahara; some will display a dotted line between Morocco and the Western Sahara; some will extend the borders of Morocco to the North of Mauritania, completely erasing the Western Sahara. The different variations of these maps can be read as geographical representations of the contentious political conceptions of the Western Saharan conflict. These maps, however, obscure the nuanced nature of this space, its tenuous borders, and mobility within and beyond them. On the process of map-making and the purpose maps serve, James Scott writes: “complex reality must be reduced to schematic categories.”[1] No map can fully capture the differing experiences of Sahrawis and the opposing forces of power that converge to shape their experiences. For a general assessment of the space in this area, however, the following maps diverge from dominant cartographic representations, especially when used to consider the folds of power and control that play a role in the everyday lives of Sahrawis.

[The above image is a map of the Western Sahara and the surrounding areas. Image from PBS.]

Unlike the traditional maps of this area, this map depicts a number of elements that are critical in understanding the conflict, such as the 1,600 mile sand berm, the distinction between the land that Morocco controls and the land that the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) government controls, and the location of the refugee camps within Algerian borders. Missing from this map, however, are the specific indicators of where the refugee camps are situated, how they are collectively configured, and the presence of military checkpoints in Algeria. For example, the following map indicates the location of the refugee camps (in red triangles), and the respective cities they are named after from in the Western Sahara, which are denoted by the blue dots. Noting how the refugee camps are named after major cities refugees were displaced from and how the geography of these camps was constructed so that it may play a role in the preservation of a collective memory is a way in which Sahrawis respond to hegemonic cartographic representations of their land. Similar to the above map, however, military checkpoints inside the Algerian territory are not illustrated.

[The above image is a map depicting the Western Sahara, the surrounding areas, as well as indicating the location of the main refugee camps in southern Algeria outside of Tindouf. Image from UNCHR.]

These maps are useful for considering a number of critical questions on the Western Saharan conflict, namely: how power is asserted through architecture and the management of space; how power is challenged and resisted through the creation of new architecture in managed spaces; and how certain spaces (refugee camps) are created with the intention of impermanence. This first article in the ongoing series examines the 1,600-mile sand berm.

The Sand Berm

During the middle of the armed conflict between Morocco and the Polisario Front, which lasted from 1975 and up until 1991 with a cease-fire, Morocco began construction of a sand berm in 1981. According to the Oxford Dictionary, a berm is “an artificial ridge or embankment, such as one built as a defense against tanks.” The berm extends from within Moroccan territory and through the Western Sahara, separating the territories that Morocco controls (to the west of the berm), and those that fall under the Polisario’s control (to the east of the berm). The final result of the berm is a 1,600-mile structure, manned by Moroccan soldiers in various posts, and an estimated seven million land mines. Polisario soldiers are positioned in several points on the other side of the wall.

[View of the berm as you approach it from afar. Image by author.]

[View of the berm from the closest point, right along the barbed wire fence. Between the fence and the berm is land littered with land mines. Ahead, on top of the berm, Moroccan soldiers can be seen standing. Image by author.]

Getting to the wall from the Dakhla refugee camp is a several hour drive, requires an armed escort from the Polisario army, and involves passing through an Algerian military checkpoint where soldiers verify travel and/or identity documents. The passage through the Algerian military checkpoint marks the end of Algerian territory and the beginning of Polisario controlled territory. Between that point and the wall is an approximate twenty to thirty-minute drive on an unpaved road marked with various objects that serve as signposts. This road also leads to the wall where landmines have either been previously detonated or removed. At a certain point approaching this portion of the berm, the Polisario armed escort remains behind as the rest of the party continues. This is done in order to avoid instigating an armed confrontation with the Moroccan soldiers stationed at the berm, as explained to me by our driver, who works for SADR department responsible for hosting foreign visitors.

Approaching the berm is an eerie undertaking. The closer we got, the more visible the berm appeared—looking like a distant mound of sand, it grows in height and length the closer you get. We were constantly told to stay on the marked path once we get out of the vehicles. “Do not venture far…the mines.” Stepping out of the vehicle, it is difficult not to reflect on the lives that were lost on this same ground, the people that were injured, and the tens of thousands of would-be Sahrawi refugees that crossed it beginning in 1975. You are unnervingly reminded of this upon the realization (and constant reminder from others) that it would only take a couple of steps beyond the marked paths to detonate a land mine.

[One of several marked landmines, surrounded by a ring of rocks in front of the berm. Image by author.]

About fifteen feet in front of the berm is a barbed wire fence that marks a no man zone, where even more landmines are scattered. As we approached this barbed wire fence, Moroccan soldiers standing atop and behind the berm began scurrying. Notebooks, binoculars, and cameras began appearing in their hands. What was initially a group of no more than five visible soldiers multiplied to about ten, then fifteen. Two soldiers approached as close they could without stepping beyond the berm where the landmines were, and began filming us. Another soldier on the phone can be heard saying, “They are mostly foreigners.”

[Moroccan soldiers with their binoculars on top of the berm. Image by author.]

[Moroccan soldiers using recording devices behind the berm. Image by author.]

The berm has been compared to the Berlin Wall and the Israeli Separation Wall, both in its sheer scope and the divisional purposes it serves. While international observers refer to it as a berm, Sahrawis do not call it a berm; they call it Al-Jidar, the Wall. At over 1,600 miles and with seven million land mines, perhaps a monstrosity is a more apt label. The Sahrawi narrative on the berm is centered around the stories of people who lost their limbs to the explosion of a mine. Morocco’s justification for constructing it—thanks to military, financial, and technical assistance from the United States—was to ward off attacks from the Polisario during the height of the armed conflict. The path of the berm extended beyond the internationally recognized territory of Morocco and into the non-self-governing territory of the Western Sahara.

By the time of its completion around 1987, the berm took on another life and evolved into serving other purposes besides “security.” Years after the armed conflict has ended, it has evolved into serving as a physical and militarized reification of the borders Morocco seeks to eventually claim as its own. Additionally, with the already sealed borders between Algeria and Morocco, it effectively stifled mobility among the Sahrawi population. Families with members living in the Moroccan controlled territories and refugee camps now faced more than just borders as a source of separation, but the materialization of a physical barrier. It has forced Sahrawis to rely on air travel as the safest means of moving between the camps and the territory, something that requires the resources and ability to obtain travel documents and an airplane ticket. With no direct flight from Laayoune and Tindouf, the travel requires at least one layover. An alternative is for separated families to meet in Mauritania, which similarly requires expending resources that are not equally available to all Sahrawi families.

As one of the most invasive and violent forms of Morocco’s extension of power, the berm has been a source of mobilization and action among Sahrawis living in the refugee camps. One such example is the group called Al-Sarkh Ded Al-Jidar, the Scream Against the Wall. The group stages monthly protests in front of the wall, where images and footage are taken, then published and disseminated online, and reprinted in posters that are displayed for the public. Unlike a brief march or demonstration, these protests last days where its members pitch tents just beyond the berm. Another example is the work done by Moulud Yeslem, a Sahrawi artist. Yeslem has led and organized the project “Por Cada Mina Una Flor”—For Every Mine a Flower, which collects flowers with written messages of solidarity with Sahrawis and plants them in front of the berm. These examples illustrate the cultivation of a new form of resistance Sahrawi youth have adopted to express their opposition to Morocco’s policies. Even as refugees distant from the Moroccan police truncheons, arrests, and torture that Sahrawis living in the territories continue to face, they are not idle in their reaction to the restriction of mobility. The tactics of forging a new resistant counter space in the face of an encroaching authority is an ongoing development and should not be discounted.

[Sahrawi artist, Moulud Yeslem, plants flowers in front of the berm as part of his "For Every Mine a Flower" project. Image by author.]

[Flowers in front of the berm. Image by author.]

[1] James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

![[View of the Sand Berm built by Morocco that separates between territory the Moroccan government controls and the territory the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) controls. Image by author.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/ScreenShot2014-05-15at3.18.35PM.png.jpg)